How ‘Les Misérables’ Can Help You Vote Your Conscience

Isn’t it obvious? Shouldn’t we vote our conscience?

Yes, I realize that “conscience” has become a coded mantra of the #NeverTrump movement. But when I heard in June the exhortation to “vote your conscience,” it made total sense. As a civic duty, voting should follow conscience.

A few weeks later, then, I was shocked when the Republican National Convention crowd booed Senator Ted Cruz’s conclusion: “If you love our country . . . stand and speak and vote your conscience.” Hearing members of the party of family values, law and order, and tradition rail at the idea of voting one’s conscience struck me hard, even though I recognized the phrase’s new double meaning.

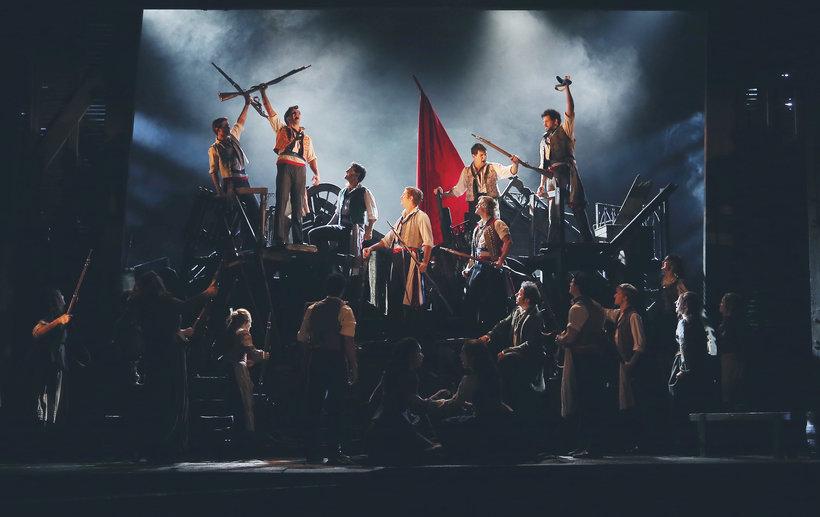

No doubt, I’m particularly sensitive to the question of conscience. I’ve been exploring what it means to live a life of conscience, a journey inspired by the popularity and inspirational quality of Victor Hugo’s Les Misérables—both his novel and the award-winning Boublil-Schönberg musical built from his story. It’s a story of conscience, in which the hero, Jean Valjean, finds and then follows his conscience—but not without ongoing struggle.

You may know that struggle―what Hugh Jackman, who played Valjean in Tom Hooper’s 2012 musical movie Les Misérables,rables called “that incredible moral dilemma”: Does Valjean turn himself in for breaking parole, or does he let an innocent man who resembles him be condemned to life at hard labor?

What at first seems a fairly obvious moral choice—save the innocent man—quickly reveals itself to be much more complicated. If Valjean gives himself up, he will hurt the hundreds of employees his business supports. He will abandon the orphaned Fantine and Cosette, whom he promised to protect. Really, can’t he do more good in the world by remaining free?

In the end, Valjean appreciates the real dilemma: Does he save his life and freedom at the cost of destroying his soul? Implicit in this question are mighty complexities and heartbreaking ironies. Valjean knows that doing the honest thing would save his soul—but would make him repugnant to the rest of the world: imprisoned, reviled, “condemned.” If he keeps quiet, he would be, from God’s perspective, “damned.”

Valjean chooses to bow to his conscience, and his choices in the face of obviously painful outcomes make him admirable. So inspirational that Hugh Jackman—who starred in 2012 musical movie Les Misérables—told me that playing Valjean made him “want to be a better man . . . every day.”

When Victor Hugo put Jean Valjean into impossible moral dilemmas, he knew from experience the complexities of conscience. As a legislator, Hugo refused Louis Napoléon Bonaparte’s coup d’état on December 2, 1851. Overnight Bonaparte had declared himself president without term, dissolved the National Assembly, and had over eighty legislators arrested. He was on his way to becoming Emperor Napoléon III. Along with other lawmakers, Hugo fought this one-man takeover of the democratically elected French Republic. As he put it, “Obeying my conscience is my rule, a rule with no exceptions.”

Sticking his neck way out, Hugo posted throughout Paris—over his name only—a proclamation urging the army to oppose the coup. That won him a 25,000-franc price on his head (about $125,000 in today’s dollars). Encouraging workers and other Parisian fighters, Hugo saw massacres by government troops, who blew up barricades and carried out summary executions. When it became clear that the fight for the Republic had failed, Hugo’s conscience offered unpleasant options: prison, death, or exile.

Hugo endured exile for nineteen years, eleven years beyond Napoléon III’s general amnesty. Despite his love for Paris, Hugo stuck to his guns, declaring, “True to the commitment I made to my conscience, I’ll share to the bitter end freedom’s exile. When freedom returns, I will return.”

Most of us are not called upon to risk a chain gang or execution by following our conscience. Still, presidential election stakes can be tremendous. With an act as crucial as voting, we each have the sacred responsibility to stand up for our beliefs.

To vote our conscience, we need to know what we believe will best serve our nation moving forward. At this historical turning point, we must ask ourselves—as Jean Valjean and some public servants have asked themselves—“Who Am I?”

Conscience. Let’s not lose the essence of such a powerful word, not even in the heat of jockeying for immediate political advantage. “Vote Your Conscience” signs should mean what they say. Hugo knew it: Conscience, he said, is like “having the moon of God in our minds.”

September 2, 2016 (The Huffington Post webpage)